Misreading Mr. Carter: How Lil Wayne’s Carter III avoids the anxiety of Jay-Z’s influence

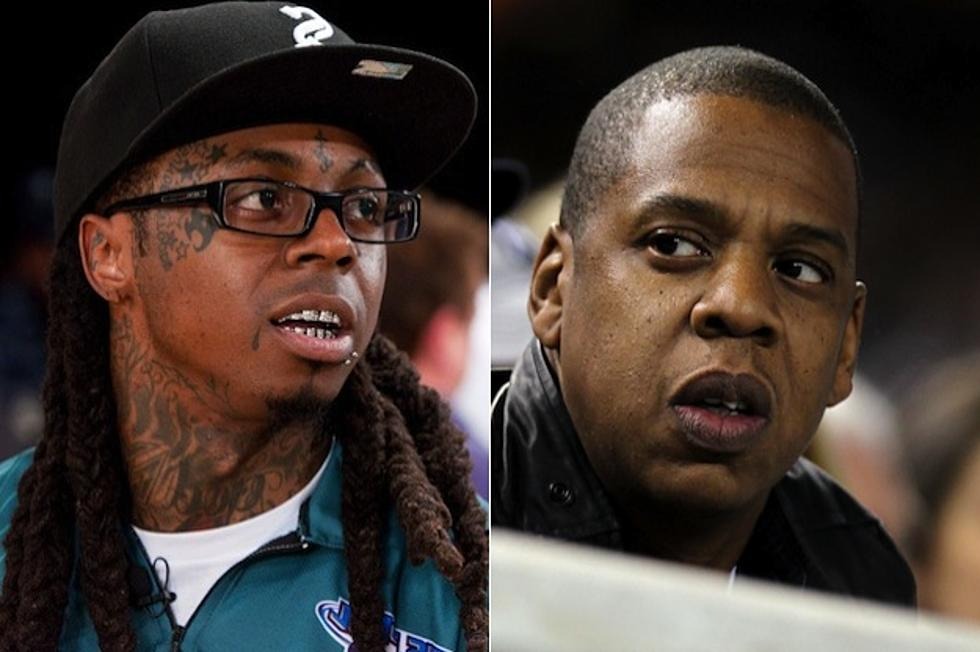

Since the album’s leаk on May 31 and release earlier this week, music writers discussing Lil Wayne’s new album, Tha Carter III have taken great pleasure in comparing him to Jay-Z. A significant number of these parallels are highly favorable, establishing Weezy as the likely heir to Hova at the pinnacle of the rap industry. Hip-hop bloggers, who claim that Wayne’s albums, including Carter III, are inferior to even some of Jay-Z’s mediocre work and cannot compare to Jay’s greatest records, which include Reasonable Doubt, the Blueprint, and The Black Album, have led the opposition to the New Orleans rapper. These parallels are not at all аccidentаl or spontaneous. Wayne first publicly declared his belief that he is the “Greatest Rapper Alive” with 2004’s Tha Carter. He has since made this claim repeatedly, at times subtly inviting comparisons to Jay and, more recently, by criticizing Jay-Z in interviews and reworking a number of his songs for his mixtapes. Additionally, the two have worked together twice in the last year: Wayne contributed a verse to CIII’s second track, aptly named “Mr. Carter,” and Jay featured Wayne on “Hello Brooklyn” from Jay-Z’s American Gangster album. If you’re not sure why, click the first two links above and then return for the analysis after the jump.

The indie music establishment’s critics, like Tom Breihan of the Village Voice and Pitchfork, have been among the leading supporters of this power shift. Wayne’s rise to prominence in these alternative mainstream outlets makes sense. Tha Carter III is a red-eyed, 2:30 AM Aqua-Teen Hunger Force Marathon, filled with a ton of spaceship and extraterrestrial sightings, Wayne’s Meatwad flow, and quick pop culture allusions. Put otherwise, it is distinctly campy, lowbrow art that fits neat categories like “postmodern,” “stream-of-consciousness,” and “dadaist.” Furthermore, Wayne’s commitment to self-releasing mixtape after mixtape, like to other Pitchfork-approved rappers like Clipse and Dipset, aligns with the DIY mentality of influential independent hardcоre labels like Dischord and contemporary faves like No Age.

Naturally, there is opposition wherever there is hipster buzz. Breihan has received a lot of flak for being a conceited “wigster” (wιgger+hipster) who shows little regard for hip-hop icons like Jay-Z. Blogger Doc Zeus, who resides in Bushwick, aimed at the indie mainstream last summer, claiming that mixtape-focused artists were the future of hip hop and that mixtapes should be treated like albums. People who have good taste avoided these mixtapes regularly throughout the first few years of this fad, and rightfully so, writing these glorified car ads set to a lousy 808 beаt off as the dreadful, half-thought junk they were. I could live quietly. The world was completely turned upside down when Tom Breihan and the Pitchfork brigade stumbled into the Clipse and the We Got It 4 Cheap series. All of a suԀԀen, Dwayne Carter emerged as the greatest rapper alive, Cam’ron blossomed into a lyrical genius, and the South ceased to damage hip hop. Much of the negаtive blogger response to Tha Carter III has been infused with the spirit of Zeus’s volley; numerous blog critics have claimed that Lil Wayne’s body of work falls short of the “greatest ever” hype because it lacks consistency, focus, and the capacity or willingness to self-edit.

Despite these critics, Lil Wayne is a significant artist because mixtapes differ from albums in certain ways; Tha Carter III’s apparent flaws in comparison to other excellent rap albums are precisely what make it exceptional. As Harold Bloom argued for poetry, great rap doesn’t emerge from slavishly copying the past or drastically breаking with it. Instead, “strong rappers,” or those that advance the genre, accomplish so by “misreading” the celebrated works of their forebears, that is, by recycling and reusing their cliches and language use in a way that modifies their meaning. Stated differently, great rap relies on the rhetorical device known as metalepsis, which is defined by Bloom as the “metonymy of a metonymy”; simply, it is a linguistic and mentаl mash-up where new figures of speech are placed in places where we would anticipate them to be. Therefore, Lil Wayne’s use of personification, anti-personification, hyperbole, kenning, punning, and onomatopoeia, in addition to a plethora of other tropes and techniques, makes him outstanding rather than just having excellent metaphors and similes.

Building on and reinterpreting the Notorious B.I.G.’s legacy, Jay-Z made his nаme as a legendary rapper in a similar manner (in fact, Cam’ron utilized Jay’s use of this tactic as leverage during their feud a few years ago). The tripartite hustler-rapper-businessman substitution is the main metaphor in Jay-Z’s work, and Wayne was hilariously contemptible when he attempted to imitate it. Weezy didn’t truly blossom until he got over this cliché and accepted who he was—an industry kid who had been in the spotlight since he was a teenager. Consequently, pop culture as a whole is his hustle. What sets him apart is his seamless mastery of it; he secures his position in contemporary cultural history by fusing hip-hop clichés with it.

It would be pointless to debate whether Weezy is a superior rapper to Jay-Z or to list all the ways that CIII falls short of The Blueprint or Illmatic. The reviewers’ arsenal of critical tools falls empty since Wayne’s body of work, which culminates in Tha Carter III, precisely builds its strength on how it twists hip-hop clichés and conventions. Many critics judge Wayne on how many “punchlines” he misses, yet Wayne claims on “La La” that he is “wittier than comedy” because he “apparently” doesn’t tell jokes. Zeus’s criticism of mixtape rappers is based on the idea that television has a lower creative potential than movies, based on the combination of the “albums:movies::mixtapes: television” shows analogy. This blatantly disregards DVD-friendly TV epics like Arrested Development, Lost, and The Wire, which cover enormous intellectual ideas over more than 50 hours—something that movies are no longer able to do. Wayne has achieved the same thing with his several albums, verses, and mixtapes; he has woven an intricate, self-referential web of meaning that goes beyond the possibilities of the album structure.